Sounds of Freedom: Michał Urbaniak Remembers Zbigniew Seifert.

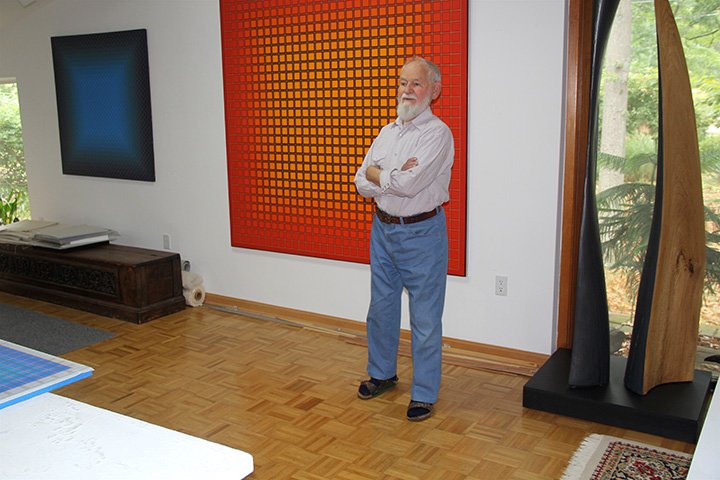

/September 11, 2017, Łódź, Klub Wytwórnia, 11th edition of the Urbanator Days 2017 music workshops. In the photo: Michał Urbaniak, photo by Łukasz Szeląg

As far as I remember, I met Zbigniew Seifert in the mid or late ’60s during a jam session at one of the clubs in Warsaw. At that time, Zbyszek was collaborating with Tomasz Stańko. He was a quiet guy, playing the saxophone. Later, he also started playing the violin, just like me – sometimes combining both instruments.

Polish jazz musicians formed a real family back then – a group of somewhat crazy and courageous people. We played jazz essentially against the system because it was banned as an imperialist influence in the communist country. Music was our whole life at the time. This clearly reflects Zbyszek’s creativity and his work. He even released an album titled Passion.

We first played together in the radio jazz orchestra in Warsaw and then had numerous jam sessions. Recordings were rare because they were controlled by the state record label. We played side by side on saxophones – he on alto and I on tenor, as well as on violins.

Seifert chose a very difficult and ambitious path, inspired by John Coltrane. He created many great pieces in this direction during his time playing jazz violin. You can hear Coltrane’s playing concept, vibe, and energy in Zbyszek’s improvisations – it’s something that comes from different periods of Coltrane’s music. Playing that kind of music isn’t easy; it’s very demanding. To start, you have to be an excellent violinist. At first, it was like a journey into the unknown.

Most of us started with the violin as children. I assume Zbyszek’s path to the saxophone was similar. He fell in love with the saxophone, just like I did, and began playing it. But later, his music became more complex and open, so the violin eventually became his second instrument, and then his primary one.

Zbigniew Seifert, photo by press materials

Both instruments are truly important to me. If I were to compare our approaches, I play more like a saxophonist, while Zbyszek played like a brilliant violinist, deeply rooted in the jazz and cultural spirit.

In the 1960s, we were already traveling abroad, mainly to Germany, although some of us also went to England and the Netherlands. I remember our performances at the Berlin Jazz Festival and other festivals – his playing was extraordinary, even grand. We also recorded together in Germany, and our project was supported by Joachim Ernst Berendt, a well-known jazz critic and producer. He also helped promote Zbyszek and his music.

After some time, I permanently moved to New York and didn’t hear much about Tomek Stańko or Zbyszek Seifert. Then suddenly, Zbyszek appeared there, recording several sessions with outstanding New York musicians like John Scofield and Jack DeJohnette. When Zbyszek arrived in New York for his first recordings, many very famous musicians were excited about him and supported him. It naturally developed from there – the music found its way to the musicians, there was simply no other possibility.

His playing, especially on the violin, was something entirely new – no one had ever gone in that direction before. It was extremely difficult and demanding, but Zbyszek was also a superb classical musician, which helped him push boundaries and achieve what he aimed for. He was a workaholic, a humble person, and his life revolved around music, constant practice, and performing.

Over time, Seifert not only developed his style but also became a leading figure in that genre of violin music. He has numerous solo albums, group recordings, and live performances to his name. The album Man of the Light was a breakthrough for him and for us as well. That album is excellent; we all listen to it more often than others. He worked every day; I remember how he would practice, play solos, and constantly improve – he was truly a dedicated artist.

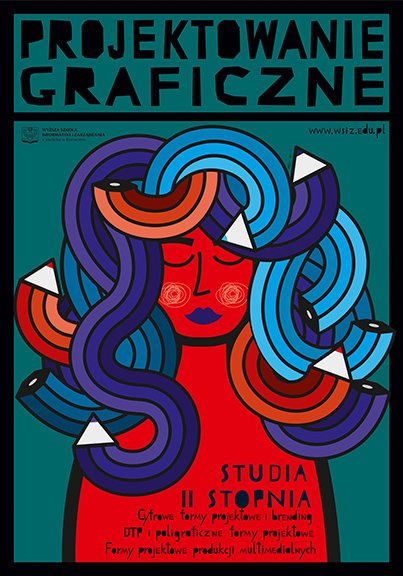

Album cover of „Man of the Light”

In recent years, I have served as a jury member at several competitions named after him, and I have noticed that many young European musicians emulate his style, both in rhythmic jazz and in the improvised European music that Seifert also performed and recorded. Moreover, playing his music is technically demanding on the violin. I have heard many incredible young virtuosos who can play in Seifert’s style. The competition rules require performing one of Seifert’s pieces, and most participants bring his spirit into their playing – people from the Netherlands, Japan, this year’s Italian violinist, and many others. Truly fantastic young violinists. Many of them can play in his style, but some also choose a more traditional approach, returning to swing and mainstream jazz.

As Coltrane once said: “Don’t imitate me, I’m searching.” Seifert was also searching for his own sounds, and so many years after his passing, he remains a source of inspiration because he was authentic.

Interview: Jacek Gwizdka

Edited by: Joanna Sokołowska-Gwizdka

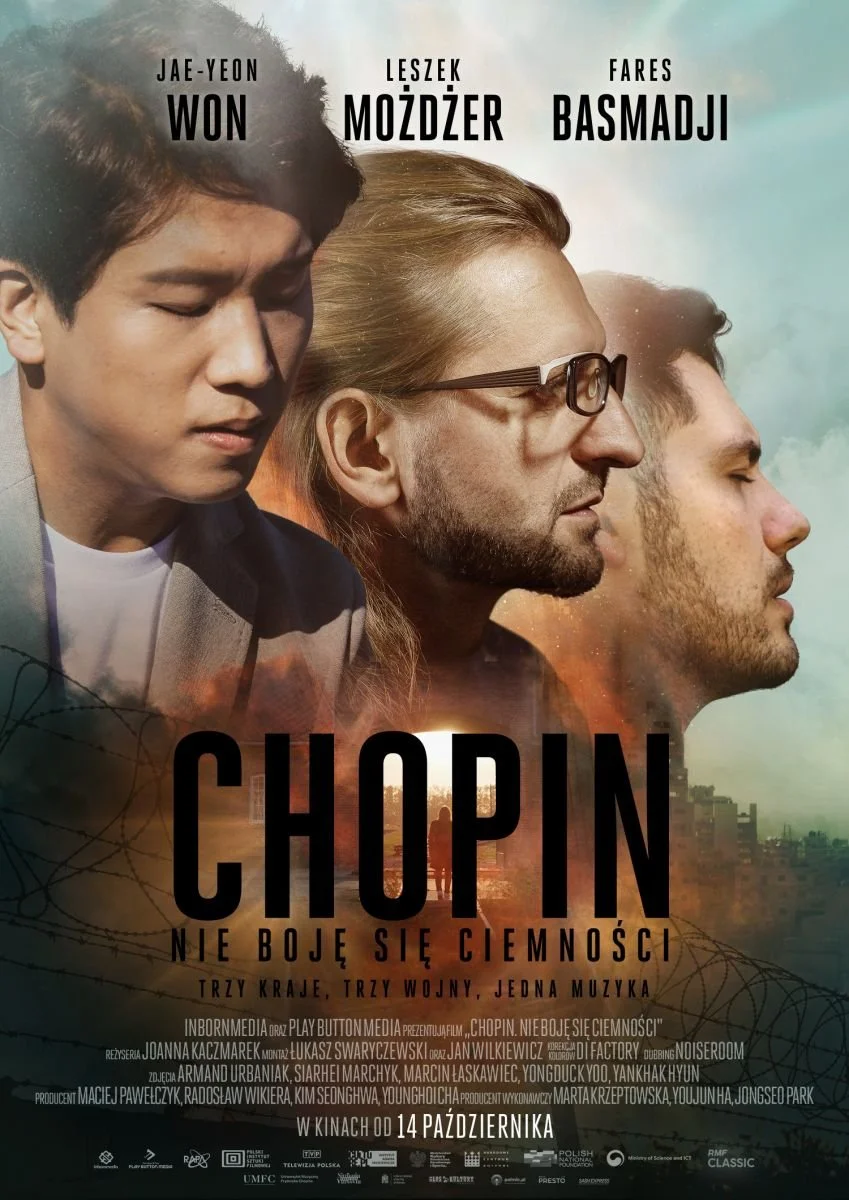

The documentary film „Zbigniew Seifert: Interrupted Journey” will be shown on November 8, 2024, during the Austin Polish Film Festival: